Hello Teapots!

Someone I work with once said that instead of “Hello World!”, I write “Hello Teapot!”.

The teapot is basically what I use to get a feel for any graphics system or technical computing platform. For example, the MATLAB teapot demo is the first thing I wrote when I joined the MathWorks, as told in my first post on the graphics blog there.

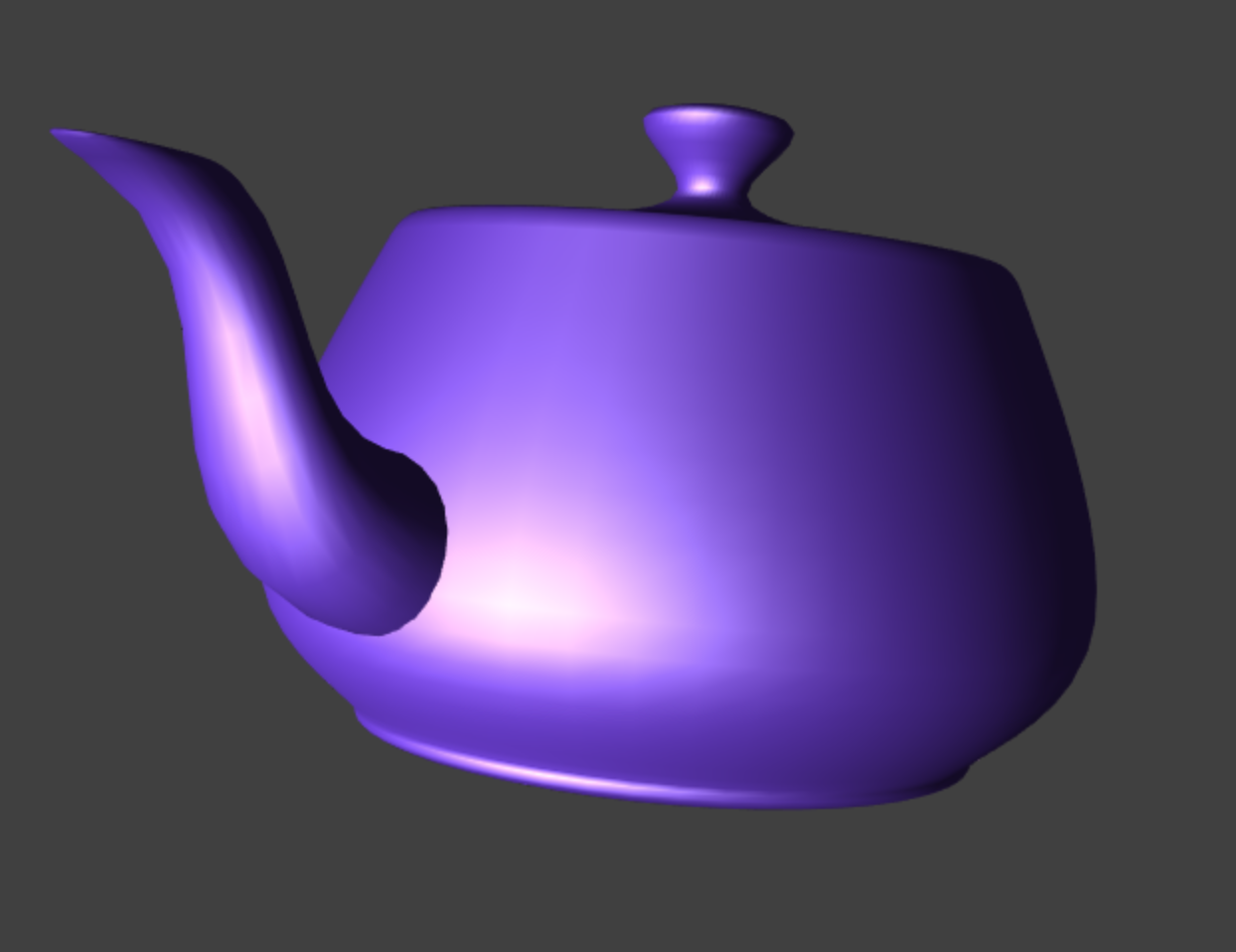

So here are a couple of recent teapots to get things rolling here at Rusty Triangles.

Rust

The first one is written in Rust and uses wgpu-rs for the rendering. This was the first Rust I’d written and is probably a bit ugly in how it’s slicing the multidimensional arrays. I like wgpu-rs. In particular, it’s shader support is pretty nice.

WebGL

The second one is written in JavaScript and uses WebGL. This is using electron to run as a local app. Numerics in JavaScript are always a bit weird. I used gl-matrix to deal with some of the worst of that. Your shaders are always an issue with WebGL. In this case they’re just strings. That means you’re probably going to have typos and cryptic error messags at startup. On the other hand, I’m more comfortable with JS than Rust at this point, and having mocha & istanbul made things go pretty quickly. I have learned more about Rust unittests since I wrote the one above.

The Math

I dug into the details of the math behind the teapot in another MATLAB Graphics blog post. Basically, the teapot is composed of 32 cubic Bézier patches. A cubic Bézier patch has 16 control points arranged in a 4x4 grid. To get a point on the patch, you substitute U & V into a 4x4 matrix composed of two copies of the Bernstein basis polynomial and multiply that by the control points.

You can take the first partials of the polynomials to get a pair of tangent vectors. The cross product of those gives you a normal vector at that point. However, as you can see in the first screenshot, this has an issue at the very top and very bottom of the teapot. There are dark “nipples” there. What’s happening there is that four of the control points are coincident. As a result, one of the partial derivative is zero length. There are a few good ways to work around that, but I often don’t bother.